Reviewed by Jaroslav Peregrin, Department of Logic, Institute of Philosophy, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Jilská 1, 110 00 Praha 1, Czech Republic.

It is uncommon to contrive a book on theoretical linguistics as a kind of a Platonic dialogue. However, the authors of Topic-Focus Articulation, Tripartite Structures, and Semantic Content have chosen to do precisely this: what they present is a dialogic confrontation of two different kinds of views of a certain aspect of language, resulting into a partial synthesis. I should say immediately that this unusual form was a happy choice; but to explain why we must return to the roots of formal semantics.

Not so long ago, people working within the post-Montagovian tradition saw their task as addressing those aspects of expressions which are independent of how and in which contexts the expressions happen to get employed. Everything concerning concrete utterances and their contexts, so the story went, is to be relegated to pragmatics (considered as something necessarily less rigorous, and thereby somewhat less ‘noble’ than semantics). However, over the last few decades it has become increasingly clear that to draw any sharp boundary between semantics and pragmatics within natural language is inherently problematic; and that turning a blind eye on anything like contexts is bound to preclude us from being able to understand the semantics of many expressions and grammatical constructions.

The English definite article provides a good example of this development. The traditional, Russellian ‘context-independent’ analysis presents the article as, in effect, the name of a function mapping sets of individuals on their members, namely singletons on their single elements and all other kinds of sets on nothing. Construed in this way, the X presupposes the existence of a unique F. However, it is clear that the great majority of natural language locutions containing the do not in this way amount to unique existence, but rather only to unique ‘referential availability’, to unique existence within the relevant context. Thus, since the works of Kamp and Heim, contexts and the dynamics of context change figure as one of the crucial themes of formal semantics (see, e.g., van Eijck and Kamp, 1997).

This ‘pragmatization of semantics’ (cf. Peregrin, 1999) has led to semanticians’ considering and reconsidering new aspects of language, especially those previously consigned to the domain of pragmatics. A particular case is intonation and stress: many theoreticians realized that we can change even the truth conditions of a sentence by changing the intonational focus. This has initiated a boom of ‘focus-studies’, trying to develop formal models of the way a change of the focus may influence the proposition expressed by a sentence.

However, it could hardly escape the notice of the exponents of this boom that the phenomena they are now so preoccupied to account for have been studied for a long time by a traditional linguistic school, namely the school originating between the two world wars with the Prague Linguistic Circle (Jakobson, Mathesius etc.) and which still has its successors in Prague (and elsewhere; cf. Luellsdorf et al., 1994). Of course, the conceptual framework of the representatives of this school differs substantially from the conceptual equipment of current formal semantics; however, that formal semantics would profit from accommodating their results appeared to be self-evident. The trouble was that the prima facie substantially different conceptual frameworks constituted a serious hindrance.

And here is where we should seek the roots of the current book with its unusual form. Barbara Partee, one of the leading figures of the post-Montagovian formal semantics, confronts her views with those of Eva Hajièová and Petr Sgall, two outstanding representatives of the most formal wing of the current Praguian linguistics, and they work together towards a synthesis. And although they have not managed to go all the way to it, the report of the convergence of their doctrines makes very interesting and extremely instructive reading.

Partee’s point of departure is the idea that we could account for the topic-focus articulation in terms of her tripartite structures, which amount to a kind of ‘generalization of generalized quantification’. From the viewpoint of the theory of generalized quantifiers, we see a sentence like Some boys smoke as stating that the extensions of its two terms (boys and smoke) stand in a certain relationship determine by its determiner (some). Partee’s idea now is that topic and focus could likewise be seen as denoting sets of some kinds of entities being in a relation which is either determined by an overt focalizer, or is a default one. Thus Boys SMOKE, BOYS smoke, Only BOYSsmoke would all come to be seen as stating that the class of boys and that of smokers stand in a specific relationship. (Partee presented the idea of a tripartite structure and discussed its application to topic and focus in a number of papers; see, e.g., Partee, 1991.) This, in effect, presupposes a categorial analysis of syntax in the Montagovian vein.

On the other hand, Hajièová and Sgall work within the framework of dependency syntax - they see the meaning of a sentence in the form of a tree, called tectogrammatical representation, which contains no non-terminals and captures the dependential structuring. Every element of the tectogrammatical structure is either contextually bound or contextually nonbound. All the contextually bound items depending on the main verb, together with everything that depends on them, and together with the main verb - if this is contextually bound - then constitute the topic of the sentence; the rest of the sentence constitutes the focus. Hence the topic/focus classification is exhaustive: every element of the sentence belongs either to the topic or to the focus. To illustrate these notions, let us take an example from Sgall et. al. (1986, p. 190-1):

(1) Tomorrow I’ll give a student some BOOKS.

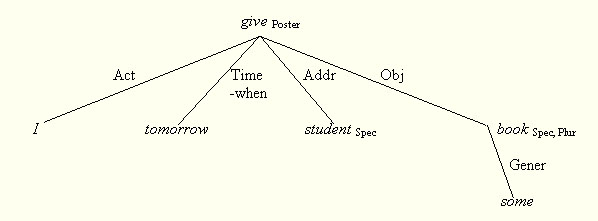

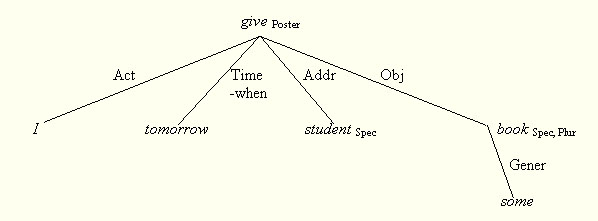

The tectogrammatical representation corresponding to this sentence is the following:

In a context in which (1) is given as an answer to the question What will you do tomorrow?, Tomorrow and I come to be contextually bound; whereas all the other items stay nonbound. Hence in this case, Tomorrow and I constitute the topic of the utterance, whereas the focus is constituted by give, student, some and book.

Thus, the ‘Praguian’ concept of focus (and the complementary concept of topic) is not identical with the concept of focus as an ‘intonationally highlighted item’ (BOOKS in (1)). The Praguian notion is based on the assumption that ‘intonational highlighting’ is not the focus itself, but rather that it is only one of various possible ways of marking focus. From this viewpoint, ‘intonational highlighting’ is merely a means of indicating focus when it is in a marked position; and another way of indicating focus is word-order (referring of course to languages like Czech, which permit this).

Now the book records a process whereby these two very different standpoints approach each other: from the initial exposition of the two conceptual frameworks in Chapter 2 (Towards an investigation of the relation between topic-focus articulation and tripartite structures) and the inventory of which assumptions the authors share and which divide them in Chapter 3 (Remarks on common background and shared assumptions), it proceeds to overcome Obstacles to joint work (Chapter 4) via a Dialogue, progressing towards a common basis for discussion (Chapter 5) to the proposal and examination of common hypotheses (Chapter 6: Some hypotheses proposed and examined) and further to outlining Future directions (Chapter 7).

What are the hypotheses the authors reach regarding topic-focus articulation? They concern two principle issues:

(i) The recursivity of topic-focus articulation (TFA). Whereas Partee’s original idea was that the articulation, being a case of the tripartite structure, must be unrestrictedly recursive in the way these structures are, the view of Hajièová and Sgall was that TFA is a matter of merely the sentence as a whole. The hypothesis to which the authors ultimately converged is closer to the latter view; they conclude that “embedded TFA happens (if and?) only if there is an embedded clause” (p. 164). In Chapter 6, the authors discuss many cases which may seem to constitute counterexamples and argue that all of them are reconcilable with the hypothesis.

(ii) The very possibility of viewing TFA as a tripartite structure and the determination of the scope and focus of the focalizer (focus-sensitive operators, like only). The basic idea entertained in the beginning of the work by Partee was that “the counterpart of the focalizer is the Operator, that of its background is the Restrictor, and that of its focus is the Nuclear Scope” (p. 162); and this idea proved to be, in the course of the book, in principle tenable. This implies that the focalizer can be seen as denoting a relation over a ‘Boolean algebra’: thus, e.g., the sentence Only BOYS smoke is true iff the set of boys stands in a certain relation to the set of smokers. In this particular case, the relation is such that not only is the former set to be included in the latter one; it is, moreover, to ‘exhaust’ it (due to the effect of the focalizer only). This means that the set of boys is to conicide with that of smokers.

A related problem is how a sentence is parsed into the topic, the focus and possibly the focalizer, i.e. into the parts corresponding to the three compartments of the tripartite structure. Here the authors reach the hypothesis which can be articulated in dependential terms as “the scope of a focalizer is the maximal projection of the head on which it depends” (thus, “the focus of a focalizer consists of the elements of the scope of the focalizer that are more dynamic than the focalizer itself”), or in terms of LF as “the scope of a focalizer is its c-command domain” (pp. 164, 165).

In this way, Hajièová, Partee and

Sgall reach a stage in which they are able to formulate substantial theses

intelligible from within both the conceptual framework of formal semantics

and that of the ‘Prague School’, thus overcoming their apparent ‘incommensurability’.

In this way, they provide for a substantial interconnection of the two

perspectives: they clarify how, in principle, it is possible to integrate

the ‘Praguian’ insights into the framework of formal semantics; and, conversely,

how methods developed within formal semantics can integrate with dependential

syntax and with ‘tectogrammatical’ semantics. There remain, to be sure,

issues in which the authors, as the representatives of the perspectives,

have not managed to reach a consensus; and even the partial rapprochement

they have achieved has yet to be fully systematized. However, I think we

should keep in mind that there are terrains where securing the safe foundations

for a house is no less difficult than building the house itself.

References

Luelsdorff, Philip, Jarmila Panevová and Petr Sgall, eds., 1994. Praguiana 1945 - 1990. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Partee, Barbara, 1991. Topic, Focus and Quantification. In: S. Moore and A. Wyner, eds., Proceedings from SALT I, 257-280. Ithaca: Cornell University.

Peregrin, Jaroslav, 1999. The Pragmatization of Semantics. In: Ken Turner, ed., The Semantics/Pragmatics Interface from Different Points of View, 419-442. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Sgall, Petr, Eva Hajièová, and Jarmila Panevová, 1986. The Meaning of the Sentence in its Semantic and Pragmatic Aspects. Prague: Academia.

van Eijck, Jan, and Hans Kamp, 1997. Representing discourse in context.

In: Johann van Benthem and Alice ter Meulen, eds., Handbook of Logic and

Language, 179-238. Oxford: Elsevier and Cambridge (Mass.): MIT Press.